Python Basics - Numbers and Functions

Today we're going to take a tour of basic Python data types and how to assign them to variables. We will discover integers, floats, and more. Learn how to use them effectively with the interactive interpreter and Jupyter Notebooks.

This tutorial assumes you have at least Python 3.6 installed. You can watch this video on Getting Started with Python (opens new window) on how to get up and running.

Note

In the regular article of this tutorial, the code entered into the

interpreter is shown in code blocks marked with py in the upper right. The

output is displayed in a code block immediately below, without the py marker.

You can view the notebook version of this article on

GitHub (opens new window)

You can also download the notebook and run it on your machine by cloning the repository (opens new window).

If you installed Python through Anaconda ipython and jupyter are already

installed. However, they can also be easily added for free from any Python

installation. Use these commands in your terminal or command prompt:

pip install ipython

pip install jupyter

Some topics we will introduce in this article:

- numbers

- integers

- floats

- math operations

- variables

- functions

- the

help()command - importing additional tools

- checking types

# Using Python as a Calculator

You can use Python just as you would a calculator. This may be an extreme approach to calculating a tip, but it's the simplest interaction to start with. You can add, subtract, multiply, and divide numbers with ease. We will build on these basics.

TIP

You can add comments to your code by using the # symbol. Anything after # on

the is just a note for you the reader and will not be executed as code.

# This is not considered code

# Addition

5 + 10

15

# Subtraction

10 - 3

7

# Multiplication

4 * 3

12

# Division

20 / 2

10.0

Notice that last one? 10.0 instead of 10. We'll cover this more in just a

bit, but the division operator / will always return a number with a decimal,

called a float, rather than a whole number, called an integer. There's

another division operator for floor division that always returns the whole

number part.

# Floor Division

20 // 3

6

# Exponentials

5 ** 2

25

Remainders from division can be calculated using the modulo operator %.

Yes, I just called it a percent sign too. 😎 So we can stay cool.

# Remainder

10 % 4

2

We can use parentheses ( ) to form more complicated expressions and control

the order of operations.

# A more complex expression

3 * (5 + 3)

24

# A more more complex expression

(3 * ((5 % 2) * 3)) + 1

10

# Intro to Variables

What if I want to store the result of my calculation to use later?

Great question! 💯

We can store our hard-earned result in a variable.

# Variable assignment

x = 2

x

2

x equals 2? Not exactly. The = operator is the assignment operator.

There is another operator for equality == that compares two values, which we

will cover in another tutorial.

The assignment operator says: give the variable, which we named x, the

value of 2. Now, wherever we use variable x it will be as if we typed 2

instead.

x + 3

5

x + x + x

6

You get the idea.

# Naming Variables

You can name a variable whatever you like, as long as it doesn't start with a number or contain certain special characters, like spaces or quotes. For example:

OK:

my_variableimportant_variable6_mooseBIG_CATsmallDog

WON'T WORK:

no spaces"airquotesbad"99numbersCantGoFirst

Let's store the value for that more complicated expression

# Give the variable named 'my_important_result' the value of the expression.

my_important_result = (3 * ((5 % 2) * 3)) + 1

my_important_result

10

To recap, the pattern looks like this:

| variable name | assignment operator | expression |

|---|---|---|

| my_important_result | = | (3 * ((5 % 2) * 3)) + 1 |

| x | = | 2 |

| y | = | x + x + 3 |

You can reassign variables. Later uses of the variable will now use the new value, instead of the old

my_important_result = 200

my_important_result + my_important_result

400

# Intro to Functions

I don't want to type these complicated expressions all the time. How can I resuse my important calculations over and over again?

Great question! 🥇

Let's introduce the idea of functions. Similar to how variables can store

values for repeated use, functions can store logic for repeated use. Use the

keyword def to define a function.

def save_my_logic():

return 2 * 8

Notice the () in the function definition? They're important. Now we can

call the function with this pattern: function_name().

save_my_logic()

16

Notice the return keyword in our function definition? The function can have

any number of steps, but you will probably want to get back some value from your

important calculation. So we need to tell it to return that value. It'll make

more sense if we add a few more steps.

def save_my_logic():

x = 3

y = 4

return x * y

save_my_logic()

12

Incredible! You can see we were able to assign values to variables within our

function, and return something specific, in this case the product of x and

y. Now you can use this function as many times as you want and it will repeat

those steps for you.

new_variable = save_my_logic() * save_my_logic() + save_my_logic()

new_variable

156

# Add a Docstring to Help

Let's add some help text, or a docstring to our function to remind us what it does.

def save_my_logic():

"""Multiplies 3 by 4"""

x = 3

y = 4

return x * y

This docstring is a comment (not executed as code) that tells you or future users of your function what it does. Documentation is important in programming. Programmers at all skill levels write and use documentation, even for your own code. It isn't easy to remember what you were trying to do 6 months ago!

Here's one way to access the docstring of our function:

help(save_my_logic)

Help on function save_my_logic in module __main__:

save_my_logic()

Multiplies 3 by 4

Whoa, where did that help thing come from? It's just another function. One

that is built into Python that tells you what a function does. Notice the

parentheses in help(our_function_name)? This is another instance of calling

a function. But this time there's something inside the parentheses. That means

we are passing something as an argument into the function, which the

function will then use.

# Arguments and Parameters

An argument can be nearly any object. Values, variables, even other functions

can be arguments! Notice how we passed save_my_logic, which is a function we

made, into the help function. We did not use save_my_logic(), with the

parentheses, which would have called the function and executed it's code,

returning the value 12. In this case, we just passed the function itself. The

help function then reads the docstring we created and displays that

information to us. We can use help(function_name) on any function. Even help

itself! 🤯

help(help) # You can call help on help!

Help on _Helper in module _sitebuiltins object:

class _Helper(builtins.object)

| Define the builtin 'help'.

|

| This is a wrapper around pydoc.help that provides a helpful message

| when 'help' is typed at the Python interactive prompt.

|

| Calling help() at the Python prompt starts an interactive help session.

| Calling help(thing) prints help for the python object 'thing'.

|

| Methods defined here:

|

| __call__(self, *args, **kwds)

| Call self as a function.

|

| __repr__(self)

| Return repr(self).

|

| ----------------------------------------------------------------------

| Data descriptors defined here:

|

| __dict__

| dictionary for instance variables (if defined)

|

| __weakref__

| list of weak references to the object (if defined)

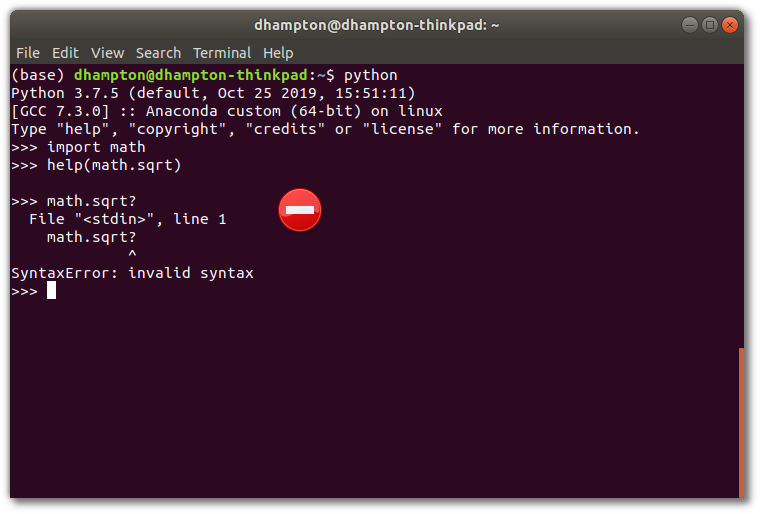

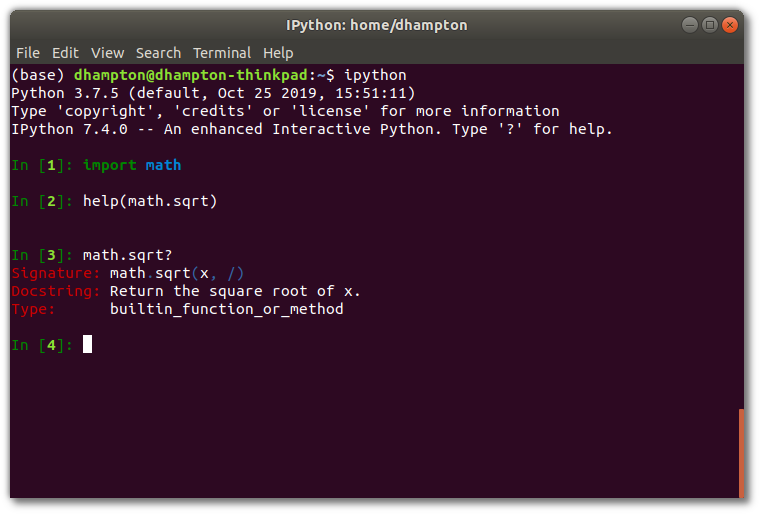

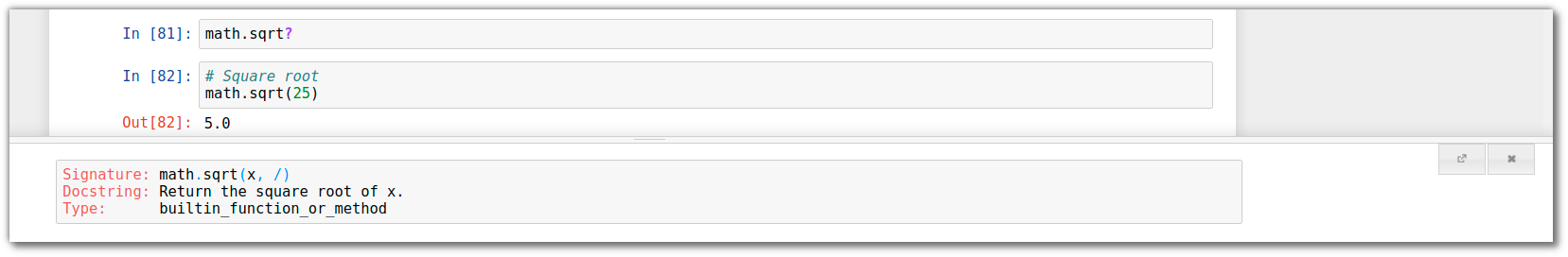

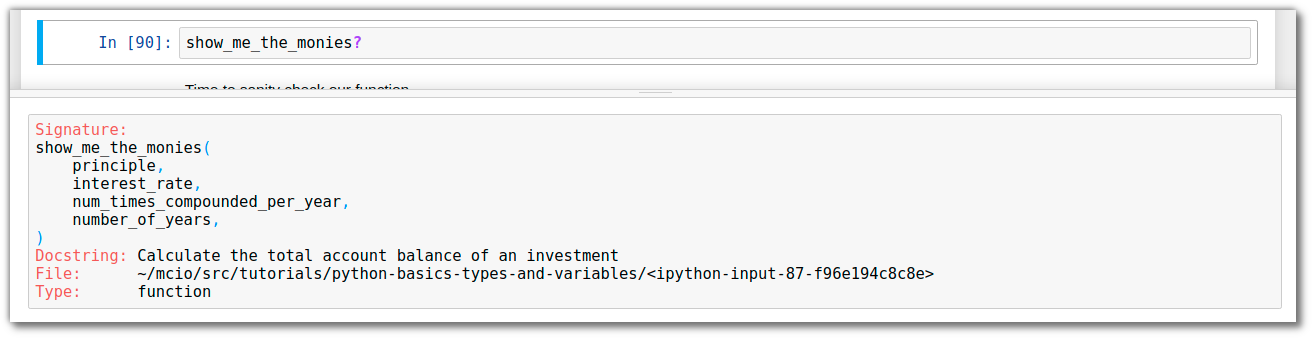

# Help Shortcut

There's a shortcut to getting documentation help. Put a question mark at the end

of the function: function_name?

If you're using the regular python interactive prompt. You have to use the

help() function.

But if you are using ipython or a jupyter notebook you can use the question

mark shortcut.

# Adding Parameters

Wait just a moment. Can I have arguments in my own functions, so I can repeat the important calculations with different numbers?

Great question! 🎱

Yes, you can. Let's make it so save_my_logic can take arguments.

def save_my_logic(x, y):

"""Multiplies x by y"""

return x * y

We have updated our function definition so x and y are no longer hardcoded

inside the function. They've been moved to within the parentheses of our

function definition. x and y are now called parameters. You can think of

parameters as the placeholders for values that will be used when the function is

eventually called.

For example, in this code snippet a, b, c are the function parameters

and x, y, z are the arguments being passed into the function when it

is used.

def my_function_name(a, b, c):

return a + b + c

x = 2

y = 4

z = 8

my_function_name(x, y, z)

Let's use our updated function.

save_my_logic(2, 4)

8

# remember you can name variables whatever you want

cats = 3

dogs = 6

save_my_logic(cats, dogs)

18

# A Real Example

All well and good, but how about a useful example instead of just adding and multiplying random numbers?

Great question! 💰

Let's make a financial formula. Everyone loves money 💵.

Calculating compound interest of an investment:

$$A=P \left( 1+\frac{r}{n} \right) ^{n*t}$$

But we can make this more readable:

$$account_total = principle \left( 1+\frac{interest_rate}{num_times_compounded_per_year} \right) ^{num_times_compounded_per_year * number_of_years}$$

Let's build this equation as a Python function with our easy to understand variable names.

def show_me_the_monies(principle, interest_rate, num_times_compounded_per_year, number_of_years):

"""Calculate the total account balance of an investment"""

account_total = principle * (1 + (interest_rate / num_times_compounded_per_year)) ** (num_times_compounded_per_year * number_of_years)

return account_total

Whew 😅.

Glad we don't have to type that out every time we want to do this calculation. Let's see this function in use.

# Set up our input data. The names of these variables do not have to match the function parameters names.

# But it's easier to follow this way.

principle = 500 # Dollars!

interest_rate = 0.05 # 5% expressed as a decimal

num_times_compounded_per_year = 1 # compounded annually, start simple.

number_of_years = 1 # start off with just a year, start simple.

show_me_the_monies(principle, interest_rate, num_times_compounded_per_year, number_of_years)

525.0

It works!

The order of the arguments passed into the function is important. If we forget

the order we defined in our function, we can call on the documentation help.

Time to sanity check our function. We expect \$500 to be \$525 after a year of growth a 5% a year (we said it is compounded once per year in the example)

500 * 1.05

525.0

Looks like it's working as it should.

How does it change if we compound it monthly? Easy to check!

num_times_compounded_per_year = 12 # changed to compound monthly

show_me_the_monies(principle, interest_rate, num_times_compounded_per_year, number_of_years)

525.5809489408665

Not a huge difference. Let's see what it would be after 2 or 3 years of investment!

number_of_years = 2

show_me_the_monies(principle, interest_rate, num_times_compounded_per_year, number_of_years)

552.4706677791635

number_of_years = 3

show_me_the_monies(principle, interest_rate, num_times_compounded_per_year, number_of_years)

580.7361156667339

There we have it. A useful example. With functions, you can reuse complex logic and easily change the inputs.

# Intro to Imports

What if I want to do some fancier math with my Python powered über calculator?

Great question! 👽

To do this, let's bring in some extra math tools (less dangerous than hammers) to help out, using what is called an import statement.

import math

What did that just do? It brought in the

math (opens new window) library, which is built into

Python. This provides us with those aforementioned extra tools 🔨. You can

import any built-in library, or you've installed with pip, by using

the import keyword, followed by the name of the library. import os for example,

to bring in more tools for working with the operating system.

Let's use the math tools we just imported. You do this by calling the

method on the math object we just imported.

# Square root method

math.sqrt(25)

5.0

We imported the library named math and called the square root method .sqrt()

with the number 25 passed to that method. A method is just a function that is

part of an object. Almost everything in Python is an object, so it's a very

general term. In this case, the imported library math is our object, and the

method is .sqrt. We access this method using the dot . notation. So a

general form would be my_object.method_name() would call method_name on

my_object.

Remember you can check what a method does by using help() or ?. For example:

math.sqrt? would show the documentation for the sqrt method.

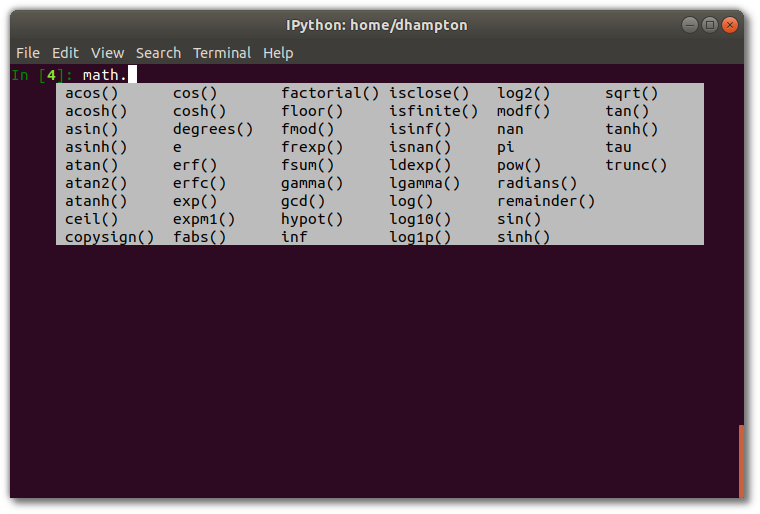

# Tab-Completion

How do I know what other tools are in the

mathlibrary?

Great question! 🛠

One way to find out is to look at the official Python documentation for the library (opens new window).

An often easier way is to use tab-completion available in ipython,

jupyter notebooks and most IDEs or code editors. If you type math. (note the

.) and hit TAB on your keyboard, it will show available methods in the

math library.

Tab completion can also be used to complete variables or functions calls.

For example, typing save_my then hitting TAB will autocomplete to

save_my_logic because we defined it earlier in our code.

Notice some of the suggestions don't have parentheses. These are not methods, but properties that represent a value. Such as the constant pi.

math.pi

3.141592653589793

# Sine of 90 degrees. We're calling the 'sin' method and using the constant 'pi'.

math.sin(math.pi / 2)

1.0

# Import Namespacing

What if I don't like typing

mathall the time to usepiorsqrt?

Great... question? 🆒

The solution is the awesome power of namespacing. Behold:

import math as m

We have created an alias for math called m. When we use m we are referring

to the math library. Namespacing just means all our math methods are

contained within the math or m namespace and must be accessed with the dot

notation. math.sqrt() or m.sqrt().

If two libraries had a function with the same name, let's say calculate, using

namespacing avoids potential conflicts. blue.calculate() and red.calculate()

refer to two different functions, both named calculate but one from

the blue library and another from the red library.

m.pi

3.141592653589793

m.sqrt(25)

5.0

Are you not entertained?

# From and All Imports

What if I don't like typing

mall the time?

... 🦍

Got you covered. If you just want to import pi and sqrt you can do this:

from math import pi, sqrt

This only imports the constant pi and the method sqrt from the math

library. You can then use these directly without having to type math or m.

sqrt(25)

5.0

pi

3.141592653589793

This is perfectly fine, as you are explicitly importing pi and sqrt and it's

obvious where they come from. Now let's look at something we should generally

avoid.

from math import *

This imports everything from math into our local namespace. This has the

potential to overwrite other methods or values in our local namespace, causing

potential confusion and bugs. I would suggest avoiding this approach to keep

things clear and readable, even if it saves a few keystrokes in the short term.

# If I'm just reading this code, how do I know where `sin` and `pi` come from?

sin(pi/2)

1.0

# Intro to Types

We have kept it simple in this tutorial by only working with numbers. There are

many more data types in Python, but before we get there, let's briefly introduce

the concept of types using the built-in type() function.

What are the types of the numbers we have been using?

type(2)

int

type(2.0)

float

You can see Python thinks there is a difference between 2 and 2.0. To review

what was mentioned earlier, the whole number is an integer and the decimal

number is called a float in Python. Otherwise known as a floating-point

value or a double in other programming languages.

type(save_my_logic)

function

Here we see that function is also a type!

type(math.sqrt)

builtin_function_or_method

type(math.pi)

float

Interestingly, the built-ins look like they have a different type, but pi is a

float as we would expect.

x = 2 + 2

When we add two integers we expect the result to be an integer.

type(x)

int

And we are correct. What happens if you add an integer with a float?

x = 2 + 2.0

type(x)

float

Notice here that Python automatically converts our integers to floats so the expression can evaluate. The result is then also a float.

You can manually convert a value between two types where conversion is possible.

float(2)

2.0

int(2.0)

2

int(2.1)

2

Notice when converting from a float to an integer we lost the information after the decimal.

What happens when we try to convert incompatible types?

int(save_my_logic)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-64-f08490dbb4cc> in <module>

----> 1 int(save_my_logic)

TypeError: int() argument must be a string, a bytes-like object or a number, not 'function'

save_my_logic + 2

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TypeError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-65-007dd7b9fc11> in <module>

----> 1 save_my_logic + 2

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'function' and 'int'

A TypeError 😱😱😱!

No worries, Python is just letting us know we can't do what we thought we could.

The important thing to know at this point is that values have types, and you can

check them using the type() function. You can also convert between types, and

certain operations like division or performing operations between floats and

integers will automatically convert types for you if possible.

# Review

That is going to conclude this tutorial, let's review what we've accomplished:

- Used Python as a simple calculator with numbers and math operations.

- Stored results of expressions in variables for reuse.

- Stored logic for reuse by creating our own function.

- Made a Python function for a financial equation using easy to read variable names.

- Learned how to access help documentation for any function.

- Learned how to import additional tools (libraries or packages) for our use in Python.

- Learned how to check an object's type, such as ints, floats, or functions.

# What's Next

In a future tutorial, we're going to look at more basic Python data types, such

as strings and booleans. We'll introduce the print function and logical

operators for comparing values.

If you want to know when the next tutorial is published, you can follow me on Twitter @DanCanDoTV (opens new window) or subscribe to the YouTube channel DanCanDo (opens new window) where the videos are hosted.

# Zen of Python

Try entering this into your Python terminal:

import this